|

By PETER APPLEBOME The New York Times Coretta Scott King, known first as the wife of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., then as his widow, then as an avid proselytizer for his vision of racial peace and nonviolent social change, died early today at Santa Monica Hospital, in Baja California, Mexico, near San Diego. She was 78. Mrs. King was admitted to the hospital last Thursday, said her sister, Edythe Scott Bagley. She died about 1 a.m., said Lorena Blanco, a spokeswoman for the United States consulate in Tijuana.

Andrew Young, the former United Nations ambassador and longtime family friend, said at a news conference this morning that Mrs. King died in her sleep. "She was a woman born to struggle," Mr. Young said, "and she has struggled and she has overcome." Mrs. King rose from rural poverty in Heiberger, Ala., to become an international symbol of the civil rights revolution of the 1960's and a tireless advocate for social and political issues ranging from women's rights to the struggle against apartheid in South Africa that followed in its wake. She was studying music at the New England Conservatory of Music in Boston in 1952 when she met a young graduate student in philosophy, who on their first date told her: "The four things that I look for in a wife are character, personality, intelligence and beauty. And you have them all." A year later, she and Dr. King, then a young minister from a prominent Atlanta family, were married, beginning a remarkable partnership that ended with his assassination in Memphis on April 4, 1968. Mrs. King did not hesitate to pick up his mantle, marching, even before her husband was buried, at the head of the striking garbage workers that he had gone to Memphis to champion. She then went on to lead the effort for a national holiday in his honor and to found the Martin Luther King Jr. Center for Non-Violent Social Change in Atlanta, dedicated both to scholarship and to activism, where Dr. King is buried.

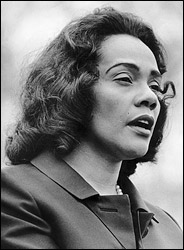

John Bazemore/Associated

Press

Coretta Scott

King, the widow of civil rights activist Martin Luther King Jr., has died.

She was 78.

In addition to dealing with her husband's death, which left her alone with four young children, Mrs. King faced other trials and controversies over the years. She was at times viewed as chilly and aloof by others in the movement. The King Center was criticized at first as competing for funds and siphoning energy from the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, which Dr. King had headed. In recent years, it has been widely viewed as adrift, characterized by intra-family squabbling and a focus more on Dr. King's legacy than on continuing his work. And even many allies were baffled and hurt by her campaign to exonerate James Earl Ray, who in 1969 pleaded guilty to her husband's murder, and her contention that Ray did not commit the crime. But more often, Mrs. King has been seen as an inspirational figure around the world, a tireless advocate for her husband's causes and a woman of enormous spiritual depth who came to personify the ideals Dr. King fought for. "She'll be remembered as a strong woman whose grace and dignity held up the image of her husband as a man of peace, of racial justice, of fairness," said the Rev. Joseph Lowery, who helped found the Southern Christian Leadership Conference with Dr. King and then served as its president for 20 years. "I don't know that she was a civil rights leader in the truest sense, but she became a civil rights figure and a civil rights icon because of what she came to represent." Coretta Scott was born April 27, 1927, the second of three children born to Obadiah and Bernice Scott. She grew up in the two-room house her father built on land that had been owned by the family for three generations. From the start there was nothing predictable about her life. The family was poor, and she grew up picking cotton in the hot fields of the segregated South or doing housework. But Mr. Scott hauled timber, owned a country store and worked as a barber. His wife drove a school bus, and the whole family helped raise hogs, cows, chickens and vegetables. So by the standards of blacks in Alabama at the time, the family had both resources and ambitions out of the reach of most others. Some of Coretta Scott's earliest insights into the injustice of segregation came as she walked to her one-room school house each day, watching buses full of white children stir up dust as they passed. She got her first sense of the world beyond rural Alabama when she attended the Lincoln School, a private missionary institution in nearby Marion, where she studied piano and voice and had her first encounters with college-educated teachers and where she resolved to flee to a world far beyond rural, segregated Alabama.

She graduated first in her high school class of 17 in 1945 and then began attending Antioch College in Yellow Springs, Ohio, where two years earlier her older sister, Edythe, had been the first black to enroll. She studied education and music and after graduation went on to the New England Conservatory of Music, hoping to become a classical singer and working as a mail order clerk and cleaning houses to augment the fellowship that barely paid her tuition. Her first encounter with the man who would become her husband did not begin auspiciously, as recounted in "Parting the Waters," by Taylor Branch. Dr. King, very much in the market for a wife, called her after getting her name from a friend and announced: "You know every Napoleon has his Waterloo," he said. "I'm like Napoleon. I'm at my Waterloo, and I'm on my knees." Ms. Scott, two years his elder, replied: "That's absurd. You don't even know me." Still, she agreed to meet for lunch the next day, only to be put off

initially that he was not taller. But she was impressed by his erudition

and confidence, and he saw in this refined, intelligent woman what he was

looking for as the wife of a preacher from one of Atlanta's most prominent

ministerial families. When he proposed, she deliberated for six months

before saying yes, and they were married in the garden of her parents'

house on June 18, 1953. The 350 guests, elegant big-city folks from Atlanta

and rural neighbors from Alabama, made it the biggest wedding, white or

black, the area had ever seen.

Even before the wedding, she made it clear she intended to remain her own woman. She stunned Dr. King's father, the Rev. Martin Luther King Sr., who presided over the wedding, by demanding that the promise to obey her husband be removed from the wedding vows. Reluctantly, he went along. After it was over, the bridegroom fell asleep in the car on the way back to Atlanta while the new Mrs. King did the driving. Mrs. King thought she was signing on for the ministry, not ground zero in the seismic cultural struggle that would soon shake the South, and her husband became minister of the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery in 1954. But just over a year later, the Montgomery Bus Boycott brought Dr. King to national attention and then, like riders on a runaway freight train, the minister and his young wife found themselves in the middle of a movement that would transform the South and ripple through the nation. In 1960, the family moved back to Atlanta, where he shared the pulpit of the historic Ebenezer Baptist Church with his father. With four young children to raise, Yolanda, born in 1955; Martin III in 1957; Dexter in 1961, and Bernice in 1963, and a movement culture dominated by men, Mrs. King, for the most part, remained away from the front lines of the movement. But the recognition of danger was always there, including a brush with death when he was stabbed while autographing books in Harlem in 1958. What role she would play was a source of some tension between them. While wanting to be there for their children, she also wanted to be active in the movement. He was, she has said, traditional in his view of women and balked at the notion she should be more conspicuous. "Martin was a very strong person, and in many ways had very traditional ideas about women," she told The New York Times Magazine in 1982. She continued: "He'd say, 'I have no choice, I have to do this, but you haven't been called.' " "And I said: 'Can't you understand? You know I have an urge to serve just like you have.'" Still, he always described her as a partner in his mission, not just

a supportive spouse. "I wish I could say, to satisfy my masculine ego,

that I led her down this path," he said in a 1967 interview. "But I must

say we went down together, because she was as actively involved and concerned

when we met as she is now."

She mostly carved out her own niche, most prominently through more than 30 "Freedom Concerts" where she lectured, read poetry and sang to raise awareness of and money for the civil rights movement. The division disappeared with Dr. King's assassination. Suddenly, she was not just a symbol of the nation's grief but a woman very much devoted to carrying on her husband's work. Exactly how to do that was something that evolved over time. Marching in Memphis was a dramatic statement, but Ralph Abernathy, one of Dr. King's lieutenants was chosen to take over his movement. In stepping in for her husband after his death, Mrs. King at first used his own words as much as possible as if her goal were simply to maintain his presence, even in death. But soon she developed her own language and own causes. So when she stood in for her husband at the Poor People's Campaign at the Lincoln Memorial on June 19, 1968, she spoke not just of his vision, but of hers, one about gender as well as race in which she called upon American women "to unite and form a solid block of women power to fight the three great evils of racism, poverty and war." She joined the board of directors of the National Organization for Women as well as that of his Southern Christian Leadership Conference and became widely identified with a broad array of international human rights issues rather than being focused primarily on race. That broad view, she would argue, was completely in keeping with Dr. King's vision as well. And to carry on that legacy, she focused on two ambitious and daunting tasks. The first was to have a national holiday in his honor, the second was to build a nationally recognized center in Atlanta to honor his memory, continue his work and provide a research center for scholars studying his work and the civil rights era. The first goal was achieved despite much opposition in 1983 when Congress approved a measure designating the third Monday in January as an official federal holiday in honor of Dr. King, who was born in Atlanta Jan. 15, 1929. President Ronald Reagan, who had long opposed the King holiday as too expensive and inappropriate, signed the bill, but pointedly refrained from criticizing fellow Republicans like Sen. Jesse Helms of North Carolina, who continued to denigrate Dr. King, saying he had consorted with Communists. The holiday was first observed on Jan. 20, 1986. The second goal, much more expensive, time consuming and elusive, remains to this day a work in progress — and a troubled one at that. When Mrs. King first announced plans for a memorial in 1969, she envisioned a Lincolnesque tomb, an exhibition hall, the restoration of her husband's childhood home, two separate buildings for institutes on nonviolent social change and Afro-American studies, a library building, an archives building and a museum of African-American life and culture. And she envisioned a center that would be a haven both for scholars and a training ground for advocates of nonviolent social change. Even friends say it may have been too ambitious a goal. Building the center was an enormous achievement in itself. But many of Dr. King's allies, particularly the leaders of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, charged that the center was draining scarce resources from the movement. Over the years the center struggled to find its mission. Critics worried that it had become too much a family enterprise with her two sons, Dexter and Martin III, vying to be its leader. Those problems became particularly acute after she suffered a stroke and heart attack in August 2005 and the two brothers struggled for control over the center while she was recuperating. As a result, many feel it has not become the scholarly resource it could have, nor has it become a center for civil rights activism. Many supporters were saddened and baffled by the family's campaign on behalf of James Earl Ray, who confessed to the murder, then recanted and died in 1998 still seeking a new trial. After his death, Mrs. King issued a statement calling his death a tragedy for his family and for the nation and saying that a trial would have "produced new revelations about the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. as well as establish the facts concerning Mr. Ray's innocence." She is survived by her four children, Yolanda Denise, Martin Luther III, Dexter Scott and Bernice Albertine, and her sister, Edythe Scott Bagley of Cheney, Pa., as well as by her brother, Obie Leonard Scott of Greensboro, Ala. To the end Mrs. King remained a beloved figure, often compared to Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis as a woman who overcame tragedy, held her family together, and became an inspirational presence around the world. Admirers said she bore her own special burden — being expected somehow to carry on her husband's work and teachings — with a sense of spirit and purpose that made her more than just a symbol. If picking up Dr. King's mantle, in the end, was something of an impossible task, both of them described a relationship that was truly a partnership. "I think on many points she educated me," Dr. King once said. And she never veered from the conviction, expressed throughout her life, that his dream was hers as well. "I didn't learn my commitment from Martin," she once told an interviewer. "We just converged at a certain time."

For related materials click here. Copyright

2006 The New York Times Company

|